The mermaid and the octopus has become a running theme in my work.

Folklore about mermaids depicts them as having very human qualities, but at their core they are otherworldly. They belong to the sea, which is an 'other world,' the depths of which we barely understand. More humans have walked on the surface of the moon than have been to the deepest part of the ocean. It is unkown, we are naturally unequipped to traverse it, and yet we are drawn to it, and it gives us life.

Mermaids are liminal beings, and as a bisexual artist, my identity feels similarly liminal. The tragedy of mermaids in folklore is when they fall in love with humans. This ends up being a tragedy for the human, in some stories. But stories about mermaids generally tell us what happens when we liminal beings have to 'choose a side' of our identity.

For example, in many Eastern European tellings of the story, the mermaid falls in love with a human, tries to live in his world, but is ultimately punished for trying to be something she is not, and dissolves into sea foam and lives the rest of her existence in mourning. In the Baltic story of Juras māte, Mother of the Sea, she falls in love with a fisherman and takes him to her world, deep under the sea where she has a palace made of amber. The gods are angered by her crossing of worlds, and kill the fisherman and destroy her palace, shattering it into millions of teardrop shaped pieces. Ever since, the sea is a place of deep mourning and sadness - but this is framed by a liminal being of the sea whose love takes her out of where others expect her to be.

In the Disney version of the story, the authors revised the story so that the mermaid falls in love with a human and is able to overcome obstacles to become who she wants to be. She is rewarded, in the end, for her individualism and for the side she chooses. This speaks more to the Western ideals of individualism than it does acceptance of liminal identities; and keep in mind, the mermaid makes a permanent decision to keep her legs and renounce the sea forever - disposing of her liminality in exchange for love. Though it seems like a happier ending, it still doesn't necessarily support the existance of liminal beings in their wholeness.

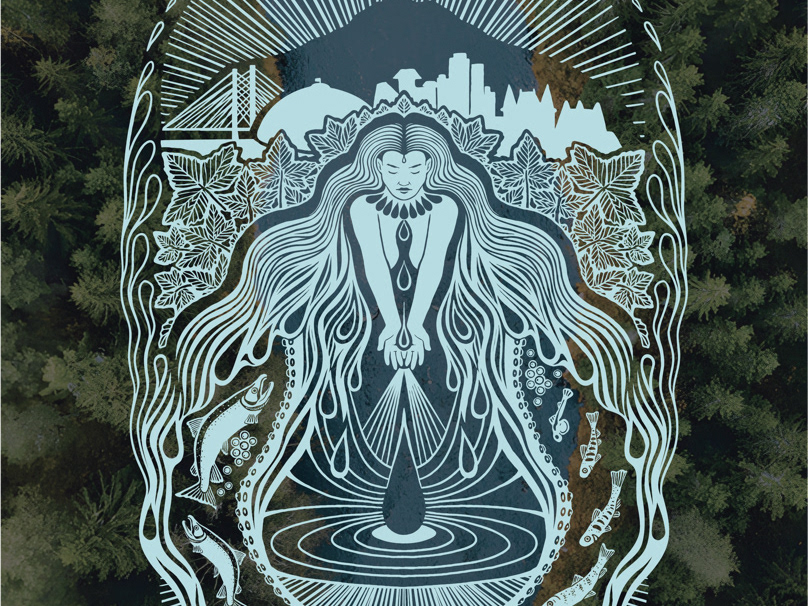

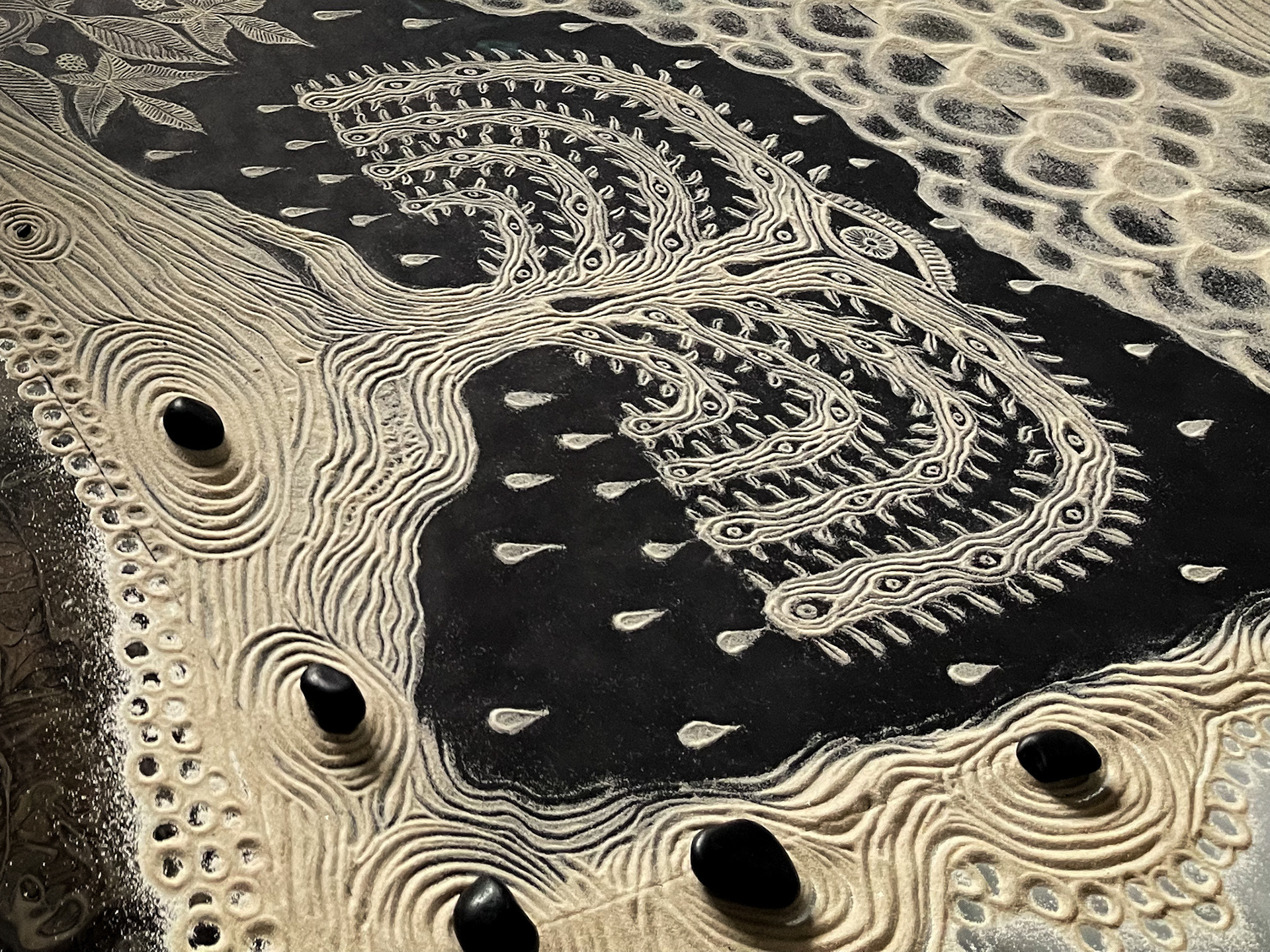

Back to the mermaid that is the subject of this painting, here we see her wrapped up and tangled in fishing nets, which represents humanity. The witness to her struggle and her sorrow is the octopus, an intelligent being who is wholly of the sea. The octopus deeply understands that part of the mermaid that is of the sea, but neither humans nor sea creatures can fully understand the unique plight she experiences as a liminal being. She feels the full weight of the pain of both sides, but doesn't fully belong to either. We can't imagine what is next for her after getting caught in the net, but we (along with the octopus) can bear witness to her existence, her pain, and her power (seen in her hand as she generates the very waters we swim in).

La sirena y el pulpo se ha convertido en un tema recurrente en mi arte.

El folclore sobre las sirenas las representa con cualidades muy humanas, pero en el fondo son de otro mundo. Pertenecen al mar, que es un 'otro mundo', cuyas profundidades apenas comprendemos. Más humanos han caminado sobre la superficie de la luna que los que han estado en la parte más profunda del océano. Es desconocido, naturalmente no estamos equipados para atravesarlo y, sin embargo, nos atrae y nos da vida.

Las sirenas son seres liminales y, como artista bisexual, mi identidad se siente igualmente liminal. La tragedia de las sirenas en el folklore es cuando se enamoran de los humanos. Esto termina siendo una tragedia para el humano, en algunas historias. Pero las historias sobre sirenas generalmente nos cuentan qué sucede cuando los seres liminales tenemos que 'elegir un lado' de nuestra identidad.

Por ejemplo, en muchos relatos de la historia de Europa del Este, la sirena se enamora de un ser humano, trata de vivir en su mundo, pero finalmente está castigada por tratar de ser algo que no es, y se disuelve en la espuma del mar y vive el resto de su existencia en duelo. En la historia báltica de Juras māte, Madre del Mar, ella se enamora de un pescador y lo lleva a su mundo que está en las profundidades del mar donde tiene un palacio hecho de ámbar. Los dioses están enojados por su cruce de mundos, matan al pescador y destruyen su palacio, rompiéndolo en millones de pedazos en forma de lágrima. Desde entonces, el mar es un lugar de profundo luto y tristeza, pero este está debido a un ser liminal del mar cuyo amor la saca de donde otros esperan que esté.

En la versión de Disney de la historia, los autores revisaron la historia para que la sirena se enamore de un humano y pueda superar los obstáculos para convertirse en quien quiere ser. Ella es recompensada, al final, por su individualismo y por el lado que elige. Esto habla más de los ideales occidentales del individualismo que de la aceptación de identidades liminales; y ten en cuenta que la sirena toma la decisión permanente de conservar sus piernas y renunciar al mar para siempre, deshaciéndose de su liminalidad a cambio de amor. Aunque parece un final más feliz, todavía no respalda la existencia de seres liminales en su totalidad.

Volviendo a la sirena que es el tema de esta pintura, aquí la vemos envuelta y enredada en redes de pesca, que representa a la humanidad. El testigo de su lucha y su dolor es el pulpo, un ser inteligente que es completamente del mar. El pulpo comprende profundamente esa parte de la sirena que es del mar, pero ni los humanos ni las criaturas marinas pueden comprender completamente la situación única que ella experimenta como ser liminal. Siente todo el peso del dolor de ambos lados, pero no pertenece del todo a ninguno. No podemos imaginar qué sigue para ella después de quedar atrapada en la red, pero nosotros (junto con el pulpo) podemos dar testimonio de su existencia, su dolor y su poder (visto en su mano mientras genera las mismas aguas en las que nadamos).